Received, A Blank Child: Dickens, Brownlow and the Foundling Hospital explored the facts and fictions that link the life and work of Dickens and the Victorian Foundling Hospital. The Foundling Hospital, which continues today as the children’s charity Coram, was established in 1739 by the philanthropist Captain Thomas Coram, as a home for abandoned babies. From the beginning artists gave their support to the Hospital, most notably the painter and satirist William Hogarth and the composer George Frideric Handel. In doing so, they created London’s first public art gallery and set the template for the ways in which the arts could support philanthropy. Charles Dickens knew the Foundling Hospital from a young age, having lived and worked nearby. He supported the institution, helping a young mother petition for a place for her child and rented a pew in the Hospital’s chapel. Dickens’ relationship with the Foundling Hospital brought him into contact with John Brownlow, the Secretary. Brownlow, himself a foundling, worked for the institution for over half a century. He was the Hospital’s first historian and created a fictional work, Hans Sloane (1831), to help publicise the charity.

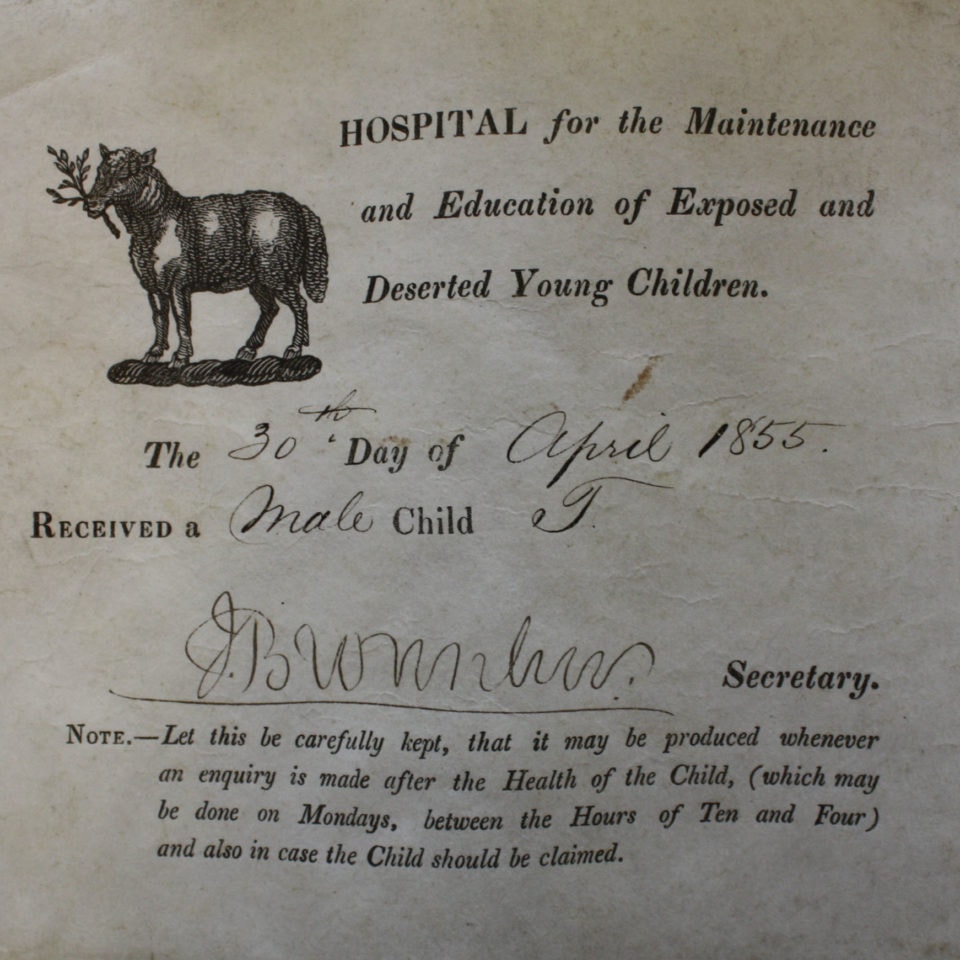

In 1853 Dickens published an article about the Foundling Hospital, Received, a Blank Child, published in his journal Household Words. The emotive title was taken from the wording used on the entry form for children accepted into the Hospital’s care. Dickens focuses on how the anonymity of each child disappeared on entrance to the Hospital and, as a ‘blank child’, he or she was absorbed into the larger social body of the Foundling Hospital. Dickens also used the institution and its children as inspiration for his fictional work, creating the foundling Tattycoram in Little Dorrit and No Thoroughfare (1867), his last stage play co-written with Wilkie Collins that concerned the imagined history of a child from the Hospital. Objects in this exhibition included letters from Dickens relating to the Foundling Hospital that have never previously been on public display, articles, journal installments, drawings, photographs and paintings by Emma Brownlow, John Brownlow’s daughter. Just as Dickens’ work continues to define our perception of the Victorian age, Received, A Blank Child: Dickens, Brownlow and the Foundling Hospital explored the facts and fictions that link the life and work of Dickens and Brownlow, illuminating the life of the Foundling Hospital during the Victorian age.